Brief Critique of Contemporary Judgement

Introduction

If there is one word that can capture the essence of the 20th century and all it represented, that word is: revolution. All the various meanings that are now attributed to the word art are a direct consequence of the gradual annihilation of the old canons of beauty that took place during that period. What we mean today when we pronounce the word art is quite different from what was meant a century ago using the same word.

This cultural realignment of society has led to radical changes that must be taken into account when attempting to make judgments about anything concerning the contemporary world:

- The destruction of all absolute rules.

- The impossibility of establishing objective standards.

- The progressive disappearance of morality.

From the ancient Greeks onward, Western tradition has attempted to unite the beautiful and the true, positioning them as a bulwark against human anguish. Contemporary art definitively destroys that ancient tradition, bringing about the sunset of what was considered absolutely immutable and untouchable—that is, absolutely true.

If the true dies, what becomes of the beautiful? What remains of its meaning?

The great artists of the 20th century—musicians, poets, writers, up to the exponents of the most modern arts such as cinema and video games—by contaminating their works with what was once considered blasphemous, have demonstrated that morality and objective canons of beauty are definitively dead. Before the twentieth century, art was synonymous with sacred art. The subjects of narratives, sculptures, and paintings were almost entirely sacred or centered on sacred stories. Those who strayed from this path were considered blasphemous heretics and persecuted by the holy inquisition. “God is dead,” Nietzsche prophetically warned.

The death of God is abstract art, all modern music—from rock (our soft-rock would once have been defined as “devil’s music”) to electronic—up to modern video games that, like their cousins in cinema, make no scruples about depicting every kind of violent language and cruel human activity, delving into the deepest viscera of the human soul, exposing our deepest emotions: love, lust, pride, violence, fear, anguish.

The Beautiful and the Ugly

When what was considered ugly or wrong according to millennial canons and dogmas begins to be questioned, to somehow be considered beautiful through artistic representation, judgment loses that charge of objectivity from ancient times and inevitably takes on an increasingly personal dimension, moving away from the objectivity required by criticism.

But how can we orient ourselves without a reference system? How can we navigate the open sea without a compass and a navigation chart? How can one remain objective and impartial? Do such words still have meaning?

When we assert that the beautiful exists, we are implicitly stating that something ugly exists on the opposite side of the evaluation system.

Beautiful and ugly are generic definitions and tell us little without a reference system. Such binary reasoning, while intuitive, proves poor and ineffective. The simple idea of beauty must therefore be surpassed to enter a dimension where it is possible to channel judgment more broadly.

The first thing to do is establish a personal coherent reference system. Just as for an Italian Germany is to the north, so for an Englishman it is to the South. Both are absolutely right according to their point of view. Criticism requires drawing up rules that allow the critic to orient themselves first, and then a type of language that allows them to communicate with their readers.

Experience and Knowledge

Let’s imagine having someone who has never listened to music hear a melodic piece. Regardless of the song, the listener will almost certainly be fascinated. This happens because a person who has never listened to music is easily captivated by the charm of the new, a charm that might not have the same effect on someone who has already listened to hundreds of musical pieces. This person, having no other terms of comparison, might generically define as beautiful everything that is new to their ears.

Every novelty adds something to our baggage of experience, just as every experience changes our way of judging. But that’s not enough. One must also know how something is made to understand it thoroughly.

Let’s say we play a very complex classical piece or an avant-garde piece, perhaps noise music, for another person with some listening experience. Suppose they aren’t particularly impressed. This happens because complexity hinders the judgment of the amateur, who as an amateur cannot move correctly on that plane of complexity.

A novice, a musician, or an avid music listener will each be able to understand certain nuances that might escape the others.

The Historical Point of View

The concepts of novelty and point of view are closely linked.

Let’s say we listen for the first time to a rock song from a newly released album. From our point of view, that is, from the listener’s point of view, that song possesses a certain amount of novelty that directly influences our judgment. But that song that we consider a novelty, when reviewed from a historical point of view, could easily reveal itself as something banal and absolutely non-innovative, even as blatant plagiarism.

It becomes evident that historical knowledge can heavily influence or even completely overturn our opinion.

Sensitivity

There is one last magmatic factor to consider: personal sensitivity.

One thing is certain: it’s impossible to quantify or define it precisely because each sensitivity is the manifestation of the sum of all cultural substrates that we carry with us from birth: they are our education, our life experience, our disappointments and our victories, our joys and our fears.

With the passing of time and the broadening of direct experience and studies conducted (from a historical point of view), we are subject to a gradual and inevitable process of de-sensitization. Consequently: the greater the experience and knowledge, the lesser the influence that sensitivity exerts on our judgment.

What happens when we watch many films, listen to lots of music, or read many books? In short, what is the obvious consequence of increasing our experience?

Think about our first kiss. The first time we do something, our emotions heavily influence the experience. We usually keep a nice memory of our first kiss, even if it wasn’t the best kiss in terms of experience. The same thing happens with books, songs, video games, or movies we saw as children: they have a special place in our heart precisely because they are associated with our first life experiences.

In judging anything, our sensitivity makes the reliability of our judgment oscillate within limits of amplitude that are directly proportional to the degree of knowledge and experience acquired.

This obviously doesn’t mean that kisses after the first one won’t be exciting anymore; it means they will be given and received with greater experience and awareness. By moving our sensitivity to a new dimensional plane, broader and more complex, we can perceive new nuances that we couldn’t have grasped as well otherwise.

Reliability of Judgment

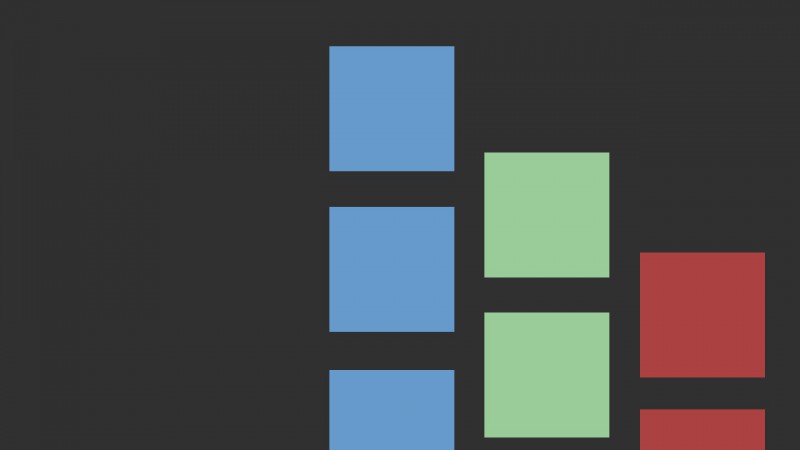

To summarize, here are the major factors that influence our opinion:

- Sensitivity represents the ground on which judgment moves.

- Accumulated experience defines the way of judging. The greater our experience, the lesser the impact sensitivity will have on judgment.

- Knowledge (understood as study) of a phenomenon broadens the vision of experience, allowing us to reach high levels of understanding.

- Assuming a historical point of view is fundamental; it can heavily influence a judgment and, in the most extreme cases, completely overturn it.

If sensitivity is the irregular ground on which we must necessarily move, experience represents the tiles we place on it, knowledge the cement that holds them together. The more accurate and solid the flooring, the more solid and accurate our judgment will be.

Divide et Impera

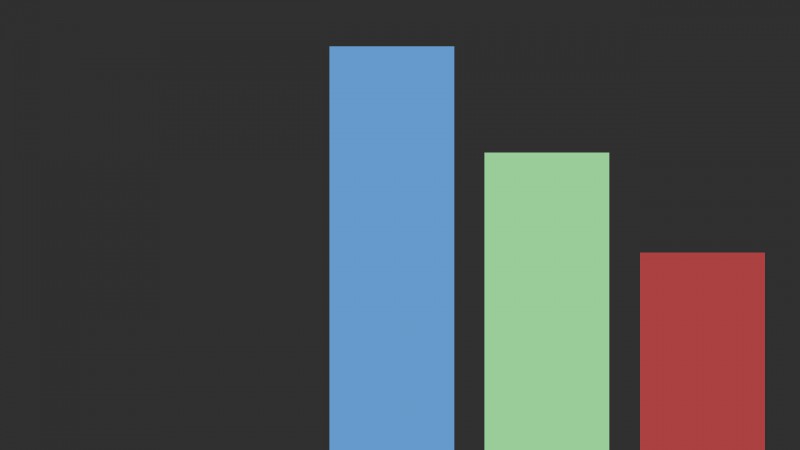

Following the old maxim “divide et impera“, we can have fun breaking down any criticism or review into classes and sub-classes of judgment.

We can, indeed, we must be able to break down a work into classes to be framed individually. It’s no coincidence that the word analysis is also a synonym for divide, separate, decompose. This type of process usually occurs at an unconscious level every day, in everything we do. Every analysis is necessarily a process of decomposition, but making it accurate is not as simple as it might seem at first glance: it requires much experience and training, as well as considerable capacity for abstraction and contextualization.

Judging a film, a song, or a video game well means knowing the history of cinema, music, or video games, the major exponents of their genres, the musical, cinematographic, or development techniques that are employed, being able to see their complexity and effectiveness, finally managing to amalgamate and historically contextualize everything.

A two-dimensional game made when 3D cards didn’t exist yet should be judged by contextualizing it to the era when it was released. Just as a film made when special effects were artisanal cannot be directly compared to a film made with the most modern digital techniques.

Similarly, a horror film cannot be directly compared to a comedy. While it’s true that they have something in common, at the same time they have very different creative techniques, purposes, and target audiences. Again, when we say that a pop album is a good pop album, it cannot be directly compared to a metal album.

Numerical Ratings

It’s not uncommon to read about people who criticize or snub numerical evaluation systems. Some professional publications have even decided to eliminate them altogether.

Assigning a grade, that is, classifying artists’ works according to an order that goes from best to worst, is a responsibility that a critic should assume.

I have always affirmed the importance of using a numerical reference system, provided of course that it is well-designed and consistent. Grades are the coordinates that allow the critic to orient themselves in the ocean of their evaluations. They are the compass that indicates direction, not destination. When the compass works, you don’t lose orientation and maintain course. With the right instrumentation, an expert critic can perform their work even better and more easily. But if the compass is broken, or if one doesn’t know how to use it properly, it becomes useless or, in the most extreme cases, dangerous.

Final Notes

A warning: we must absolutely not become cold and detached. This process of analysis and decomposition allows us to fully enjoy all the small, sometimes even imperceptible nuances of an artistic work. Let’s not forget: sensitivity will always be the vital fluid that flows between the grooves of our flooring, even if it is very solid.

Another example I like to use is that of the navigator. Sensitivity is the sea that surrounds us, experience is our vessel, which can be as fragile as a raft or as solid as a ship. Knowledge is the driving engine; from a pair of oars to a powerful combustion engine. As in the previous example, knowledge and experience are closely connected: it’s impossible to think of being able to govern a large merchant ship by arm strength alone.